3:1–7 The main plot of the book of Esther begins to unfold in Esther 3:1–15. The narrative prior to this point has been setting up events before vv. 1–6 and the developments that follow. In contrast with Mordecai’s unrewarded service to the king (2:19–23), Haman is honored, even though the narrative hints at that he should be dishonored (vv. 1, 4). By the time the narrative reaches v. 7, more than four years have passed since Esther became queen (2:16). The events of 2:19–23 and 3:1–6 occur at some point during this time period. |

3:1 Agagite A derogatory title that the Hebrew text uses to affiliate Haman with Agag, the Amalekite king. Agag was an enemy of Israel because of the Amalekites’ attack on the Israelites when they were journeying to the promised land (Exod 17:8–14; 1 Sam 15:2–3). The narrative is already revealing what type of person Haman will turn out to be—like the evil Amalekites. If the derogatory title is also meant to reveal Haman’s lineage, then it also enhances the racial tension of the story—this is a battle between Yahweh’s people and their longtime enemy.

the Amalekite king. Agag was an enemy of Israel because of the Amalekites’ attack on the Israelites when they were journeying to the promised land (Exod 17:8–14; 1 Sam 15:2–3). The narrative is already revealing what type of person Haman will turn out to be—like the evil Amalekites. If the derogatory title is also meant to reveal Haman’s lineage, then it also enhances the racial tension of the story—this is a battle between Yahweh’s people and their longtime enemy.

above all the officials Haman has supreme authority among the officials, presumably second only to the king—the narrative shows that his role is a hybrid between a chief-of-staff and a general. The Hebrew text does not reveal precisely why Haman was elevated to this role—it may have been because of an act of service or multiple acts of service over several years (compare Esth 5:11, 6).

3:2–6 In these verses, Mordecai intentionally defies Haman, even though the king has commanded that people pay respect to Haman (v. 3). The Hebrew text does not explicitly state why Mordecai makes this decision. |

3:4 they informed Haman It seems that Haman learns of Mordecai’s disobedience—which is ascribed to Mordecai’s Jewishness—secondhand; Haman then seems to witness it himself in v. 5.

3:5 was not kneeling and bowing down Two different terms for kneeling or bowing down—neither term implies any sort of payment or religious practice.

3:6 he considered it beneath him The Hebrew text here is vague about why Haman chooses to not punish Mordecai alone. Verse 5 suggests being Jewish is Mordecai’s excuse for not bowing, but that still does not justify the absurdity of Haman’s logic—to punish all Jewish people for one person’s decision.

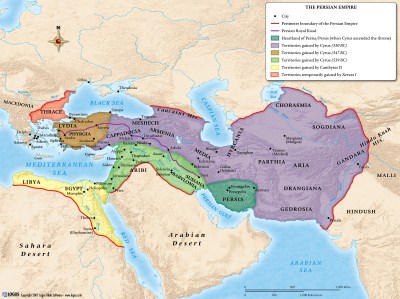

the kingdom of Ahasuerus Refers to the entire Persian Empire.

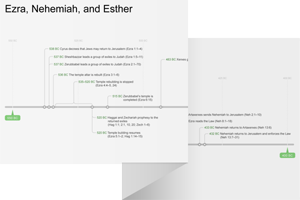

3:7 the month of Nisan, in the twelfth year of King Ahasurus March or April 474 bc. More than four years have elapsed since Esther became queen. At this point, Esther is not truly reigning as queen—in terms of authority, she is still in an uncertain and rather weak position (see 4:11).

Israelite Calendar Table

Israelite Calendar Table

pur—that is, the lot The Hebrew text uses the Akkadian term for casting lots, pur, to explain the name of the Jewish festival Purim, which will be referenced in ch. 9. The events in this verse are not occurring over a year-long period, but instead involve an elaborate game of chance occurring over multiple days to determine a specific date in the year. It appears that someone else is casting lots on Haman’s behalf, although the Hebrew text does not yet reveal what date Haman is determining, although v. 6 hints at his intentions.

the twelfth month, that is, the month of Adar The month that the casting of lots dictated, which is equivalent to February or March. In Esther 3:13, it is revealed that Haman was using the casting of lots to determine the date for the destruction of the Jewish people. The date of the genocide is set for about eleven months from this moment in the narrative.

3:8–15 Now that Haman has conspired, he visits the king so that he may put his evil plan into action. |

3:8 a certain people An intentionally vague reference to the Jews.

scattered and separated among the peoples A result of the deportations of the Jewish people by the Assyrians and Babylonians

and Babylonians (2 Kgs 15; 16; 24:10–17).

(2 Kgs 15; 16; 24:10–17).

do not observe the laws of the king Haman seems to be drawing a false conclusion from his experience with Mordecai (see note on Esther 3:6).

3:9 to destroy them Haman calls for the annihilation of the Jews throughout the Persian kingdom. This type of action was not without precedence in the Persian Empire.

ten thousand talents of silver This is a ridiculous sum, equating to at least two-thirds of the annual income into the royal treasury from all tributes in the empire (compare the historian Herodotus’ remarks in Histories, 3.95). Haman may intend to pay this out of his own abundance of wealth or, more likely, from the bounty he will gain when he destroys the Jewish people (compare 4:7).

3:10 signet ring The face of these rings included an engraving that would be utilized to stamp an image on a document, particularly when sealing it. This functioned as the king’s personal identification symbol. During the Persian period, signet rings were commonly imprinted on wet clay or wax that was allowed to dry, thereby sealing documents such as scrolls. The imprint of the king’s signet ring essentially served as his signature.

3:11 The money is given to you The Hebrew text here could be interpreted as the king telling Haman that the money is unnecessary—this would be a way of bargaining with Haman (acting like the money is Haman’s to do with as he wishes). This could also be a subtle way of the king acknowledging that he will receive the money later on (as a type of bribery).

as you see fit The king seems more concerned with his reputation and the obedience of his subjects than with the execution of the plans. The king’s immense trust in Haman at this moment—providing him with the ability to write and approve the specifics of a directive on his behalf—is yet another absurd move by the king in the narrative.

3:12 the king’s secretaries Those who were charged with writing on the king’s behalf. These are not necessarily professional law-makers; they could be copyists.

in the first month on the thirteenth day On the day before the Jewish Passover in 474 bc, the decree is sent to each major government leader in the Persian empire that the Jewish people were to be annihilated on a single day (compare Exod 12:6).

3:13–15 The method used for deploying the decree in vv. 13–15 is nearly identical to that used in 1:19–22—a parallel likely intended to highlight the king’s ridiculousness. |

3:13 the month The genocide was set to happen in February or March 473 bc (9:1). The decree is sent out about eleven months before its planned fulfillment, but it would have taken approximately three to four months for it to reach the entire empire. However, Mordecai and Esther would have had nearly the full eleven months to prepare, presuming that Mordecai learned about it early on, since they were already in the primary capital of the empire (v. 15).

plunder their goods It seems that Haman is incentivizing the genocide with monetary gain; he may also specifically mention this in his decree so that he can fulfill his bargain with the king (v. 9; compare note on v. 11).

|

About Faithlife Study BibleFaithlife Study Bible (FSB) is your guide to the ancient world of the Old and New Testaments, with study notes and articles that draw from a wide range of academic research. FSB helps you learn how to think about interpretation methods and issues so that you can gain a deeper understanding of the text. |

| Copyright |

Copyright 2012 Logos Bible Software. |

| Support Info | fsb |

Loading…

Loading…